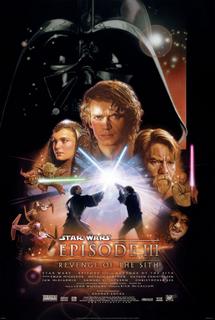

In the 16th Century, Doctor John Faustus sold his soul to the Devil in order to gain special powers and secret knowledge. There in a nutshell is the legend told many times by the likes of Christopher Marlowe, Goethe, and most recently George Lucas. How could the considerate and clever little chap who just wanted to help in Episode I devolve into the emperor’s enforcer with the remote control chokehold we met back in 1977 (Episode IV)? How could the love struck teenager whose romantic heart ached for Padme Amidala become the monstrous destroyer of worlds who pulls the trigger on the Death Star cannon? As Episode III reveals, he made a deal with the devil.

In the 16th Century, Doctor John Faustus sold his soul to the Devil in order to gain special powers and secret knowledge. There in a nutshell is the legend told many times by the likes of Christopher Marlowe, Goethe, and most recently George Lucas. How could the considerate and clever little chap who just wanted to help in Episode I devolve into the emperor’s enforcer with the remote control chokehold we met back in 1977 (Episode IV)? How could the love struck teenager whose romantic heart ached for Padme Amidala become the monstrous destroyer of worlds who pulls the trigger on the Death Star cannon? As Episode III reveals, he made a deal with the devil.There is no end to the critical reviews of this movie. I intend to limit my critical comments on the “magic” of this film to two wonderful uses of setting. Anakin’s complete descent into the Dark Side takes place in Hell. The planet Mustafar in all of its lava-rich digital glory stands in for the Hadean realm. The confrontation with Padme and the battle with Obi-Wan Kenobi that leaves Anakin horribly disfigured could not take place anywhere more fitting. It just wouldn’t have the same impact if it were to take place on the planet with the Ewoks. Likewise, I thought it appropriate that Palpatine/Darth Sidious should use the senate chamber as a weapon in his duel with Master Yoda. Setting is an important element in all six films of the Star Wars series, but I believe it plays a most significant role in this film where it backlights the crucial turn of the saga.

What about the "light" of this movie? What message does it communicate? The content of the story continues Anakin’s obsession with control and power which is developed in the previous films (see earlier entry). Anakin fears loss. He is filled with anxiety over a premonition of his wife, Padme, dying in childbirth. The fear motivates him to acquire power, specifically the power to save her life. The anxious need for power and control places Anakin in conflicts between doing what is right and doing what he wants. Adding to the conflict and complexity is pride. Anakin is insulted by discipline from the Jedi Council and their reluctance to trust or affirm him as a fellow Jedi. These weaknesses are exploited by Palpatine, who serves as a convincing Devil in this Faustian drama.

Anakin’s struggle is presented in one of the movie’s weaker scenes, yet it is a scene worth mentioning because it gets to the core of Star Wars theology. Anakin has a “counseling session” with Yoda in which he chats with the diminutive green sage about his disturbing dreams. The scene is weak because it plays out more like a clip from Oprah as Yoda utters his views on death and passage to a higher state of consciousness. Death, according to Yoda, is just one form of life being consumed by the "life-Force" of the universe and reprocessed into all living things. In the world of Star Wars, Yoda’s point of view is reality, but his view does not necessarily have such pre-eminence in our world. Why rejoice for those who die even if, as Yoda says, they are processed into the greater cycle of life in the universe? Do not the circumstances of death have something to do with our response to death? Arguing from Anakin’s point of view, we might ask why there is cause to rejoice when his mother is brutalized by thugs. How can one accept death as natural when it is sometimes hastened by injustice, deception, and oppression? Does Yoda rejoice when all of the Jedi “younglings” are massacred by Darth Vader?

Absent in Yoda’s view of the universe is the view of death as an enemy. This view is present in Judaic and Christian worldviews, though it is not the exclusive view of death. In the Christian worldview, it is possible to regard death as something that is not natural or willed by God; rather it is an enemy or an aberration of the natural order. Like Anakin, we may struggle with questions about death and suffering, in fact we may struggle more deeply because we question what may seem to be God’s indifference. The struggle is not easily resolved, but we are given a choice between faith and fear. Christians believe that a champion, Jesus Christ, has defanged the terrible beast called death and so we no longer have to fear it and we can actually laugh in its face. Yet, we do laugh at death because of our own power to conquer the beast, rather we rely on the power of the champion. So we vest our faith in this champion, not ourselves.

The option between faith and fear is crucial to the Christian life. Fear leads us to trust in structures of power and protection that actually lead to our downfall. Like Faust, we bargain with the Devil, even if he presents himself through his agents. Like Anakin, we bargain for secret knowledge, and even though our intentions may be just, we may be tempted to pay an unjust price for the power and protection. Self-preservation masquerading as self-sacrifice is masterfully portrayed in Episode III. On Mustafar, Padme pleads for Anakin not to continue his descent into evil. He replies, “I'm doing this for you, to protect you.” To which she replies, “Anakin, you're breaking my heart!” Is Anakin really trying to save Padme, or is he trying to save himself? Is he taking a stand against the enemy or is he sheltering himself from a power that he fears could destroy him? Ironically, it is Anakin’s efforts to protect Padme that lead to her ruin and his.

The Bible is rife with stories of people who try to devise their own solutions for power and protection. They build towers, arrange for the birth of heirs, negotiate with rulers of other nations, construct religious strictures and structures, and execute prophets and messiahs who threaten their sense of safety. Ironically, these solutions become the mode of suffering and loss. Yet, God works in these disasters to bring forth new hope.

I have many other thoughts on the story that unfolds in Episode III. I am interested in the theme of trust and relationships. I am interested in the inconsistent approach to absolutes and complexities that is most apparent in this film but also prevalent in the six-part saga. I hope to share these reflections, but in the meantime, what do you think?

No comments:

Post a Comment